If I had to choose between agreement and conflict, I’d choose conflict every time—it always yields a better result. (Jeff Bezos)*

Scene I

“I don’t care, I don’t care, I do NOT fucking care!” Libby slapped the table, catching her lavender beret as it slipped from the crown of her wavy hair, the color of scorched earth.

Nine people in the meeting room stared blankly in the spaces between heads, thinking of a time when we were going to be astronauts, medical missionaries, and culinary influencers. The source of Libby’s angst was an app called “Amazon Connections.”

Every morning, via random, bot-generated questions, the program solicited feedback from employees on a variety of topics, most frequently the performance of their direct manager, in our case Libby G.**

In meetings and emails, we were coached that managers did not know which employee answered any specific question; they only received a report with a summary of ratings, usually comprising five choices, from bad to terrific, for each question. The bot flagged any “not good” rating (the numerical equivalent of a three or below) by sending it to the manager’s manager for escalation.

During breakroom chit-chat team members scoffed and ridiculed Connections. It locked your screen until you responded to the questions, which were often redundant, grammatically incorrect, and irksome. If you blew it off by, say, rating everything five stars, it began to stalk you with snarky queries like, “What is your favorite flavor of ice cream—chocolate or vanilla?”

As for the company’s claim your manager did not know names of employees, it was viewed as the Amazon version of Pascal’s wager: For a rational person it was better to believe your manager, like God, knew everything, including the names of the employees answering the questions, as one stood to increase the probability of gain (the heaven of a steady job) and limit the probability of losses (the hell of getting fired).

It came as shock, therefore, that a cadre of people in our troop (i.e., a worldwide road logistics [RLS] compliance support team, recruited to the company’s corporate offices in 2018 for the launch of Amazon’s own dedicated road logistics operation, the final leg of the “Everything Store”) had taken a direct, horns-down run at Libby via the convenience provided by Connections’ questions.

The two provoking queries were as follows: How would you rate (Libby G___’s) understanding of your work? (Rating of 2 out of 5); Over the past three months, how would you grade (Libby G__’s) ability to earn and create trust among the team? (Rating of 1 out of 5). Oh boy!

The room grew cold. It was all in the open now. The questions, in bar graph form, frozen on the screen behind Libby, were a testament to it. The glum silence an affirmation. A few people around the table stirred, folding their arms.

Libby bounced out of her chair and grabbed a marker. “Let’s talk goals!”

*Bezos, to the best of my knowledge, has never publicly attributed inspiration for this idea to William Faulkner and his famous quote, “If I had to choose between nothingness and pain, I’d choose pain every time.”

**Any resemblance to current or former employees is a coincidence

Scene II

Libby scribbled bullets and arrows across the length of a whiteboard for the next 30 minutes. She took a picture of the board and emailed it to the team as “meeting notes.”

It was the first time I felt like laughing all day.

Afterward, I ran into Dylan, a RLS program manager, in the hall. He smiled crookedly: “What a freakin’ shit storm eh?”

“It’ll get fixed,” I offered.

At a level, I believed it—or wanted to. We were only at year one into our journey down the road logistics highway. In the meantime, we were getting paid! We had signed up for this. No one expected it to be easy.

I fought my misgivings: Sure, Libby had misconstrued interviewing subject matter experts and getting feedback from stakeholders as cheating and making others do our work but she, like all of us, was learning on the job.

Yes, Brad, our skip-level manager and Libby’s boss, presided over bi-weekly meetings in which he rambled in circular trains of thoughts and obfuscations, never once articulating a clear idea or goal, but that’s what high-level managers did! If Brad could adeptly speak out of both sides of his mouth, it meant, if anything, Amazon had recruited shrewdly, we were in good hands. To say or assume that by this time there should be a semblance of structure and organization was immature and unrealistic. The chaos, like life, was temporary.

There were signs it could work. Personally, I felt, I had executed my assigned work at the highest level. In six months I had written twelve Standard Work procedures for compliance processes that didn’t exist. I herded the stakeholders, against all odds, into meetings and we slogged through every mind-numbing, tortuous step with a pencil. Weeks of follow-up meetings, emails, calls, and messaging ensued to get consensus on points. In month six, just in time for the audit by the Department of Transportation, they were complete, printed, and posted on Amazon’s Intranet site. At the audit, the Amazon compliance manager had told me, the senior DOT auditor had lauded the documents, telling the intern with him, “don’t expect anything this organized.” Indeed, in April, less than a year after being hired, I was given a raise, with Libby saying, “It’s fucking unprecedented.”

But change was afoot. As Amazon qualified more of its own commercial drivers at Facility and Sort Centers across North America, the RLS team moved floors and spaces in our building several times in less than a year to accommodate new members. Each onboarding was celebrated as a 5-star recruit signing with the Crimson Tide.

We were scrambling, problem solving, juggling, minute by minute, day by day, to stay above regulatory waters. It was, as promised, empowering, lean, no rules, and self-directed. There were potlucks, free passes to Katy Perry and Macklemore concerts, and an office bar comprising bottles of Tito’s, Chivas, and Ron Rico. Esprit de Corps, goodwill, and bonhomie prevailed.

As far as it is feasible to like one’s boss, I, we, did. Libby was witty and fun; with a genuine consideration of people heralded by her simple habit of saying “good morning” to everyone at the start of each day. With her capes, ponchos, and floppy skirts, she pulled off a reinvented, retro-80s chic that fit her persona like a glove. Having climbed some rung of the operations ladder at UPS, she exuded confidence and competence, and we could see why Amazon had tapped her to lead the company’s dedicated road logistics launch.

True, the scale, scope, and complexity of the logistics launch was growing exponentially—Amazon’s fleet of commercial drivers had grown from a few hundred to thousands in less than a year. This wasn’t UPS, where everything was built. This was Amazon, where nothing was built. Conversely, this wasn’t operations, trucks and warehouses, it was corporate, data warehouses, and deep-dive critical thinking on the creation of standards and processes. But at this level of the company, a cost center, Amazon was egalitarian, not elitist. Anyone on the RLS team who dwelled uneasily on these distinctions, was a curmudgeon, or worse, a snob.

Scene III

In the end a foreboding gut feel prevailed.

After the Connections meeting, Libby weaponized and attacked.

As recent world events show, when a power launches an unprovoked assault, Truth becomes a casualty. In our remote corner of a budding commercial empire, we experienced a demonstration of it.

Interpretation of Amazon’s job description Levelling Guides? Under Libby, this primary reference guide defining work expected and work exceeding one’s role, or “Level,” became a study in subjectivity and deconstruction worthy of French philosophy. Documented work consisting of proof of completed projects exceeding one’s job description was deconstructed (ignored), and the work or tasks expected for a job Level were subjectively sliced and diced into a thousand pieces of interchangeable, meaningless busy work—the only apparent purpose being to create overwhelming, hyperventilating-inducing workloads.

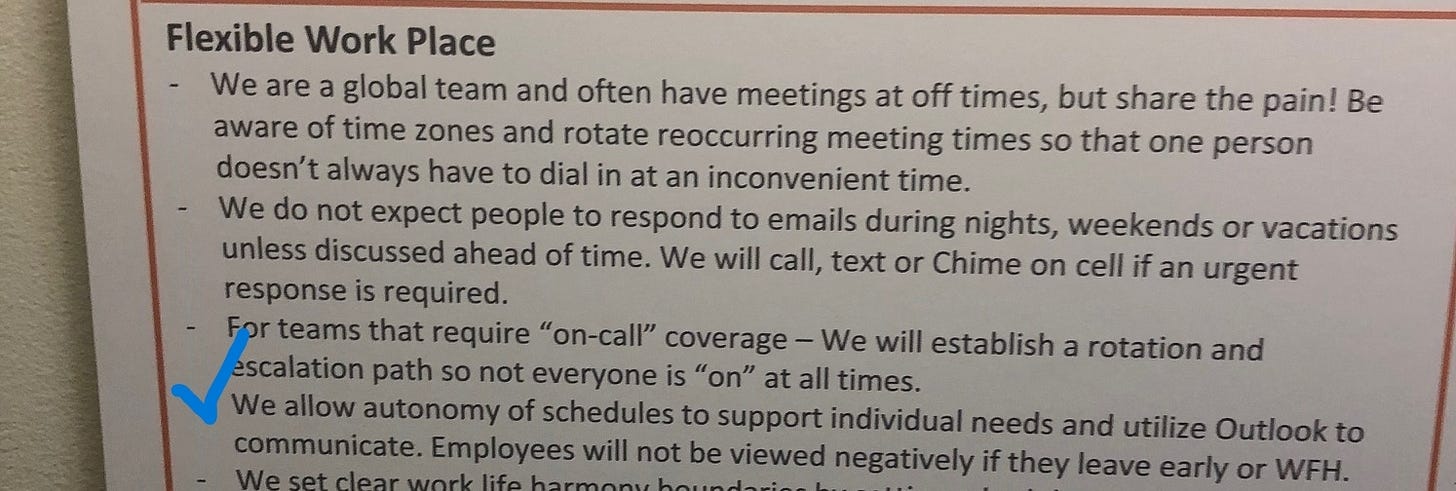

Managerial mentoring and support took on new shades of meaning. In 1-on-1 meetings, “Don’t die on that hill,” became one of Libby’s favorite, heavy-handed bromides. She would use it to escalate oversight of various made-up indiscretions, such as misuse of casual, or ad hoc remote working arrangements. When it was noted that three of the four managers on the RLS team worked remote permanently, and that flexible working was listed as one of our parent department’s core tenets in the break room (see photo), she orally acknowledged the statement via F-bomb.

Creativity and innovation were throttled. All work was distilled to layers of project management, tracking and reporting. Libby commenced a hyper-aggressive regimen of trolling team pings and micro-managing staff taken straight from the playbook of Xi Jinping. Hostile? Check. Threatening? Check. Multiple confirmed, complaints by multiple people sent to HR. Check.

One morning, as I was scrambling to assign milestones for projects in a spreadsheet, Dylan messaged me: “Libby’s gone!” Not long after, so was most of our team.

Epilogue

Libby’s tactics were rationally irrational, and, at a minimum, unethical. It was an overt, bamboozling scheme (a.k.a. “workout”) designed to set people up for failure, then can them. (There are at least two parallel stories within this story to be told in another post.)

Is it possible Amazon Connections, the tool for soliciting employee feedback featured at the start of this post, played a role in her exuberance? There is no way to prove it, but the notion is credible.

For context it is important to know that Jeff Bezos does not want people hanging around Amazon for a long time. The idea is coded into the DNA, and history, of the company.

Bezos essentially fired Amazon’s first employee, Shel Kaphan***, promoting him to CTO with nothing to do. Kaphan, whom Bezos has called the “most important person ever in the history of Amazon.com,” left of his own accord after five years. He called Bezos’ de facto ouster of him as “A betrayal of sacred trust.”

Unsentimental to the max, Bezos saw that employee turnover fostered renewable cycles of creativity and work discipline, while nipping entitlement and disgruntlement in the bud as companies got big. The question was how to build a mechanism for turnover within the company?

This is where Bezos’ genius, primarily as a student of human psychology, comes to work.

It is easy to see how Connections is a source of tension and conflict between employees and their managers, and between the managers and their managers, and so on up the food chain which, at Amazon, is usually vast and convoluted.

Leadership is a thankless job and employees are a famously disgruntled lot. Amazon managers may not know the names of employees who rate them down in Connections, but that does not keep them from guessing. Over time, as we all know, bad vibes only fester and grow, rarely heal. With a steady push from upper management, the whole thing eventually reaches a breaking point and managers gladly (if only from exhaustion) light the fuse on the forced-firing ballistics (referred to in cold-blooded terms as unregretted attrition, URA) the company constantly dangles in front of them.

***Kaphan, responsible for writing most of the UNIX code that got Amazon.com up and running, apparently griped too much for Bezos’ liking. Mr. Kaphan did not respond to my request for an interview.

Coda

High employee turnover, as a way of keeping the work force fresh and motivated, may have an irrefutable logic embedded in psychology, but there is scant evidence it provides Amazon and its shareholders benefits. The opposite argument is more convincing: the churn created by excessive turnover is fuel to the fire of the company’s inflated costs and spending.

Over the past year and a half (and prior to Amazon’s recent announcement of a 19 to 1 stock split) Amazon’s stock has lagged at roughly half the overall 15% growth rate of the S&P 500. Many analysts argue much of even that increase in Amazon’s stock price can be attributed to the 37% growth (2021) in revenues generated by AWS. In Q4 2021, Amazon’s retail business accounted for 87% of sales but zero net income. All $5.3 billion of net income was owed to AWS.1

As for Libby, I imagine she landed on her feet somewhere outside the realm of Amazonia and is doing well. By February of 2021, our road logistics team had shrunk to three people, one of which was me. I left Amazon in March of that year.

Investopedia, Matthew Johnston, February 19, 2022